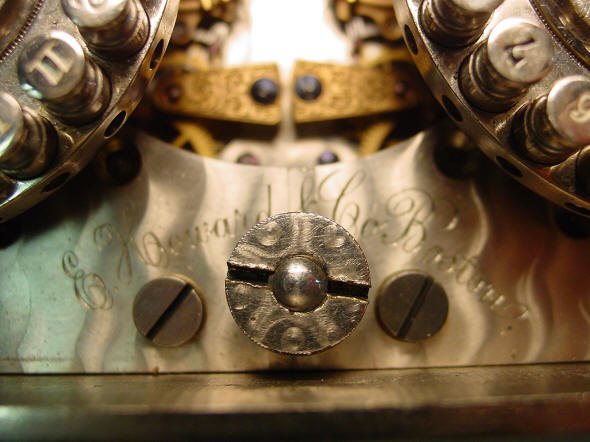

Yale Lock Manufacturing Co., Stamford, Connecticut - 2 movements, Double Pin Dial No. 3

Photo taken with glass removed.

The first photo shows a close up of the E. Howard platform escapement. Introduced in 1875 in their Model 1 this was a major design improvement from Sargent and Greenleaf's movement designs introduced in 1874 with regards to serviceability of the time lock. As described in the opening chapter describing A Brief History of the Time Lock Industry, all of the manufacturers required an annual inspection of their time locks to keep their guarantee against a lock out and this was supported by the bank's insurance company. Most often if a movement gave trouble it was located in the upper portion of the train, the balance wheel, escapement, or escape wheel. At this time S&G did not employ a module that contained these parts. Only the balance wheel was separable from the rest of the movement. The remaining escapement and escape wheel were still contained within the same set of plates that held the rest of the wheel works and main spring. Yale's design is known in horology as a 'platform escapement'. With the introduction of Yale's model #1 aka the Double Pin Dial, E. Howard employed their watch production expertise to create this for ease of service. The platform was not commonly used in pocket watches where the individual components of the upper train were not mounted to a common frame. It seems the Howard company developed this for the time lock industry, although the concept of the platform was well known prior to this time in the manufacture of carriage clocks. This feature allowed for interchangeability between movements of the entire platform assembly since the next wheel down the train was a common wheel. The very tight tolerances needed for movement components the the size of a pocket watch at this time were too tight to allow interchangeability of any of the components within any platform. Although an entire time lock movement was considerably larger than a pocket watch, the upper train components containing those parts within the platform assembly were pocket watch size. The top, transverse, mounted platforms used by Hall were not interchangeable. By the time that company was reincorporated into the Consolidated company in 1880 these still were not interchangeable until about the late 1890's. With the introduction of modular movements by Yale by 1887, S&G in 1889 the usefulness of the platform in servicing became obsolete since the safe tech could simply swap out the movements without resorting to any of the skills necessary for work on the movement itself. The defective movement would then be sent back to the firm for in-house service. While somewhat rare compared to the total numbers out there, the fact that there are many three and even four movement time locks that still have the original consecutive numbered movements is a testament to their reliability since none had to be swapped out for service. Once swapped out the original movement was rarely ever returned. Of course another option was for the bank to operate on one less movement which was possible and still quite safe in a three or four movement configuration and have their movement serviced locally and replaced when repaired. But this was rarely done as insurance requirements would not allow this option.

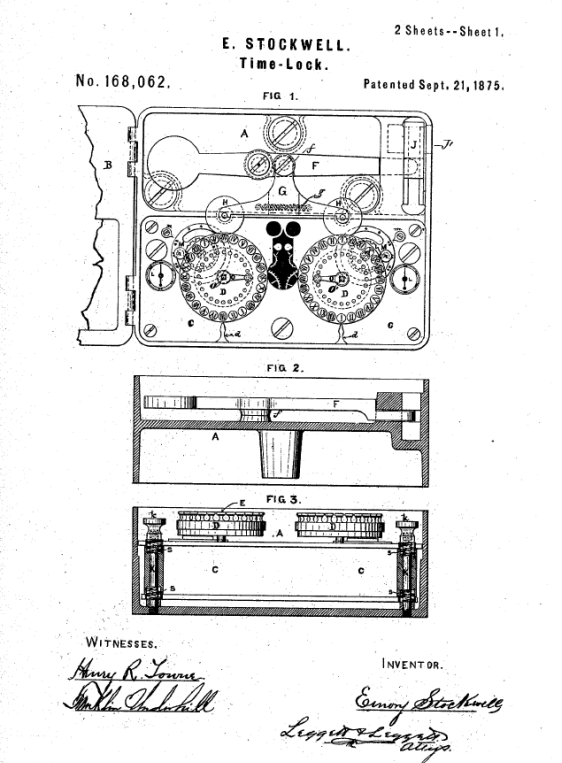

These are the drawings from Emery Stockwell's original patent for the Double Pin dial dated September 21, 1875, the same year Yale introduced their Model 1 time lock based on this design. Mr. Stockwell was one of the important inventors in the time lock industry along with James Sargent, Henry Gross and Milton Dalton to name a few. Yale Model No: 3 c.1880. Double Pin-Dial Time lock (1). This was Yale's first time lock, and is probably one of the finest, complex and more beautiful ever made. Available with either 56 hour or, after 1885, 72 hour movements. An extremely expensive item as the standard version was $400. A day of the week attachment, Sunday Attachment (2), was available for an extra $50. This lock is prior to the advent of the 'modular design' where individual movements were interchangeable. The movements were made by E. Howard & Co., Boston, one of the finest watchmakers of the period. Howard continued to supply Yale as well as other companies (Consolidated, Diebold) with movements until exiting the business around 1902. Although a complex and expensive lock, it was popular and Yale made over 2100, therefore this lock for it's age is fairly common with over 400 known survivors of which 50 have the Sunday Attachment option. However Yale offered a rebuild of the earlier 56 hour movements for $30 and many were converted, so the 56 hour model is quite rare. 7 1/4"W X 6"H X 3"D, Movement #1227, case #1321. file 100 A feature unique to this type of time lock (pin dial) is that as well as being ' off guard ' it can go ' on guard ' in accordance with the settings of the pins. As such it is designed to run continuously, unlike the majority of time locks which go off guard when they run down. However, if the movements are allowed to stop completely they will take the lock off guard, despite the settings of the pins. The description of how the pin dials work is below:

The Yale time lock contains two chronometer movements which

revolved two dial plates studded with 24 pins to represent

the 24 hours of the day. These pins, when pushed in, form a

track on which run rollers supporting the lever which

secures the bolt or locking agency, but when they are drawn

out the track is broken, the rollers fall down and the bolt

is released. By pulling out the day pins, save from 9 until

4 the door is automatically prepared for opening between

these hours, and at 4 it again of itself locks up. For

keeping the safe closed over weekends and holidays, a

subsidiary segment of track is brought into play by which a

period 24 or more hours is added to the locked interval.

Careful provision is made against the eventuality of running

down or accidental stoppage of the clock motion, by which

the rightful owner might be as seriously locked out as the

burglar.

Compare this model to the Yale single pin dial (a rarer version). Below is a Diebold safe equipped with a Yale double pin dial. The medallions are on Yale's double dial bank lock with the two sides of the Paris exposition medal of 1876 where it won silver. The portrait is of Napoleon III. This is an example of cross branding in the time lock industry. Diebold had not yet at this time entered into the time lock business so the Yale was added as an 'after market' product. What's even more interesting as that this safe used Yale equipment for the combination locks so this may have been an installation made before Diebold entered the time lock business in 1894, but this is pure speculation as branded safes, especially Diebold, often had a variety of other makers time locks installed.

An original Yale advertisement c. 1876. Notice that the time lock is upside-down! This document shows the interesting (confusing) numbering system Yale used for their Double Pin Dial models. (1) The pin dial is clearly a far more complicated design than Sargent & Greenleaf's Model 2, offered a number of innovations, the most obvious being the two front dials, each with series of twenty-four pins. Every pin, embossed with an hour of the day, could be pushed in, locking it, making the Pin Dial the first time lock capable of both unlocking and locking a safe at a predetermined time. Further the Pin Dial was the only mechanical time lock ever to be able to lock, unlock, and re-lock a safe for various one-hour periods throughout the day. American Genius Nineteenth Century Bank Locks and Time Locks, David Erroll & John Erroll, pp 164. (2) In 1876 Yale added the Sunday Attachment, which allowed the lock to skip the opening periods each Sunday. The mechanism is identified by two curved nickel runners next to the inner top third of the pin dials embossed with "Thursday Friday Saturday" and a small shield on each dial that is geared to rotate at one-seventh the rate of the dial. These shields move over the the names of the days, allowing the user to check to make sure it is accurate, and then, during the twelve hours Sunday day, will be interposed between the drop wheel and the pins, guarding the opening of the pulled pins and keeping the lock shut. This option was available after 1885. American Genius Nineteenth Century Bank Locks and Time Locks, David Erroll & John Erroll, pp 164. |