|

Overmyer and Huston, Model 1, New Lexington, Ohio

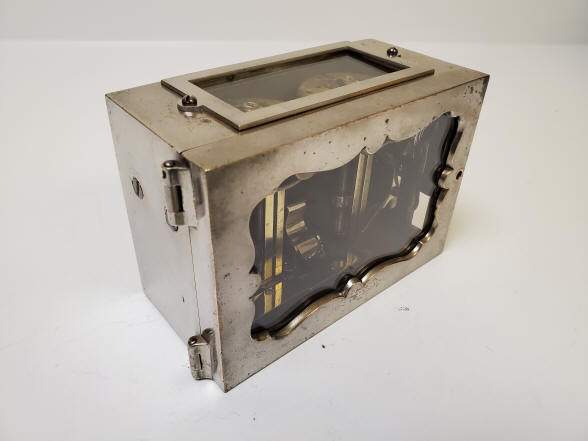

Front elevation of the lock. Notice the fancy scalloped window aperture. This author is sure that he has seen this same design on another early time lock but cannot locate it. Anyone reading this, if they have seen this design please do get in touch through my website.

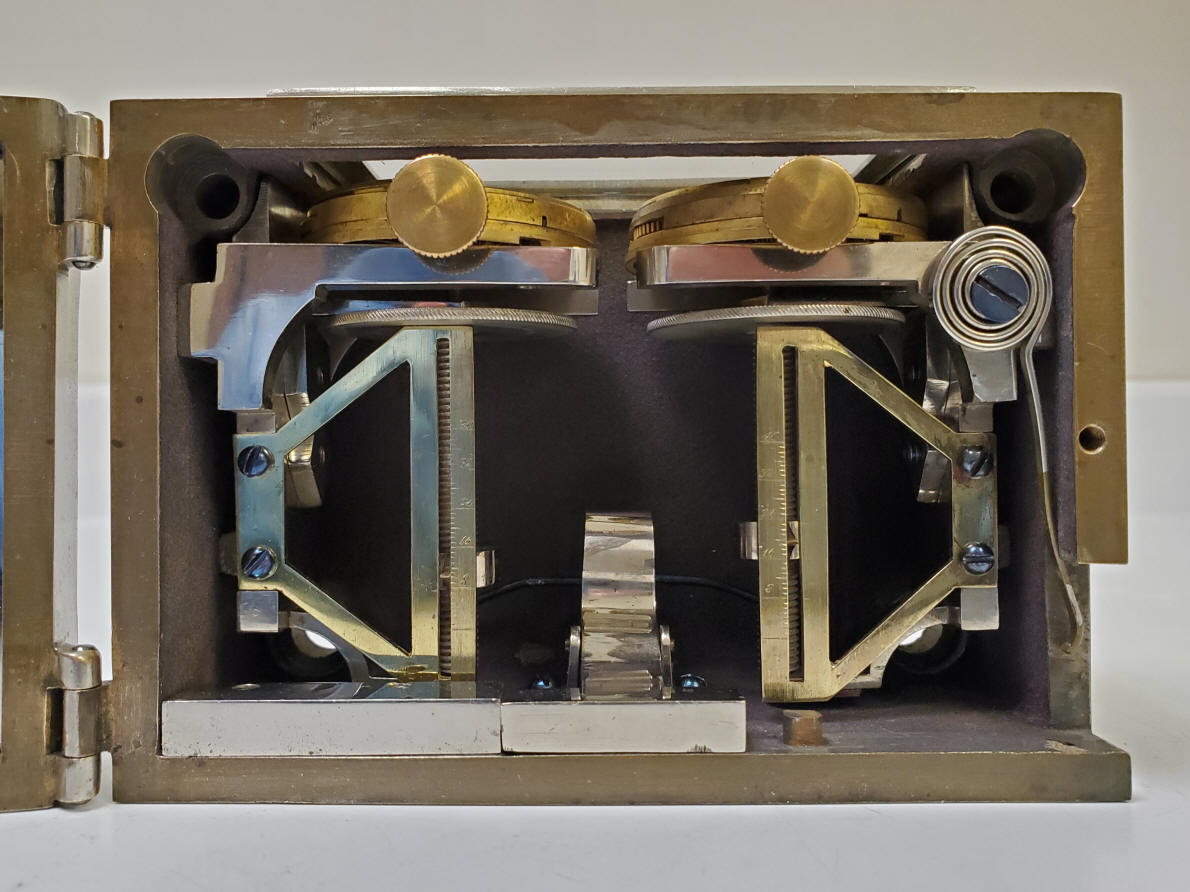

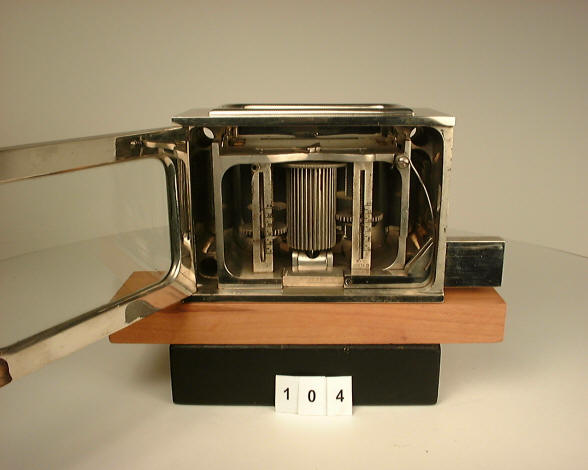

Interior view of the lock. One curious feature is the fact that the interior is lined with what once was a purple colored felt, it is now much darker. This is the first time a lock seen that has had such an interior finish. Normally the interior is either left the case metal color or if finished it is painted in "Security Red" which appeared as the inside red-orange case color of choice on many lock makers for their better, more expensive products and is seen at least as early as 1833 by many makers, long before the introduction of the time lock. The part in the center is the bolt dog. There are a pair of wires that protrude from each side. When the jack screw nut indicator reaches zero, the tail pushes the wire attached to the rear of the pivoted bolt dog backward and thereby allows the safe bolt to the right (missing) to slide under and past the bolt dog. The coil spring is biased to the right and would have been attached to the missing sliding bolt work to the safe door. The slide guide is still present attached to the bottom of the case and to the right of the bolt dog. See demonstration video.

The top elevation showing the movement window aperture. The lock uses a pair of Waltham ELLERY model 18s size pocket watch movements.

Top three-quarter elevations, left and right.

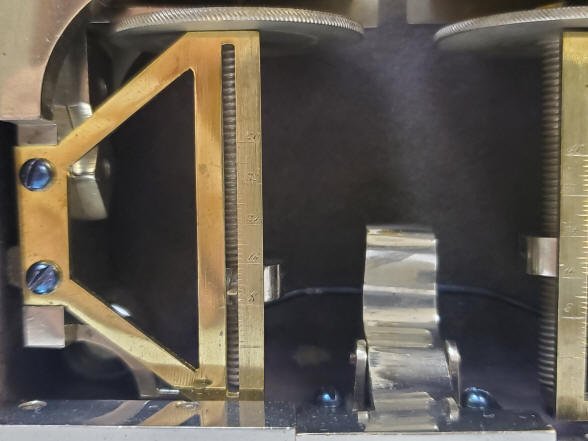

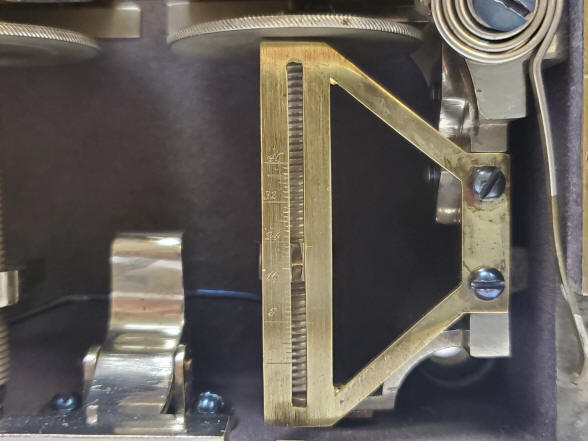

These two photos show a close up of the dial pair. On the left one can see the jack screw and the screw nut which has an indicator hand that moves vertically within the dial slot and is read off the dial, currently at hour 10, and the dial is marked from 40 to 8 in eight hour increments with the bottom mark indicating what would be zero or the time the lock is put off guard. At that time the tail of the nut opposite the indicator hand on the other side of the nut, tips the pivoted bolt dog backward setting the lock off guard. The fact that the maximum duration was 40 hours on the scale also indicates that this was never meant to operate in a commercial environment. This model of pocket watch was meant to be wound daily, and while it would have had some power reserve, would not have been more than 30 hours, and in this application, less given the additional load of the jackscrew the watch was asked to power.

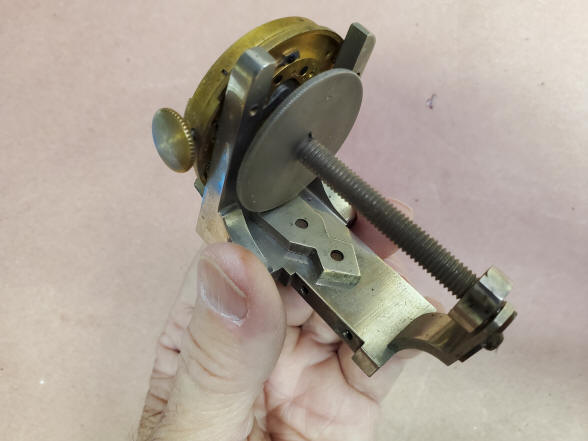

The first photo shows the profile of one of a pair of frames secured to the inside of the case. This holds the movement, knurled thumb adjustment, jack screw and nut which serves both as the timing indicator hand and trip for the bolt dog. See video for demonstration. The second photo shows the protective dust ring. Given the state of the rest of the lock as found, and the top of the movement plate the inside wheel works are nearly pristine. The dust cover was not used in Waltham's production movements fitted into a watch case and were unique to these movements. The movements run, even though they have probably never been serviced since their inception in 1876. The rest of the lock the case and internal components were given a 'light' restoration. Many of the screws were rusted and were originally blued, so these were cleaned and heat blued to their original color.

These two photos show the front and rear of the left hand movement. In the first photo one can see the key winding aperture and square have been replaced by a smooth substitute plate, see illustration below. The oversized stem winding knob is seen to the right. Next the underside shows a series of gears and a plate in silver color that allows the transition from key to stem wind. In the middle is a crank attached to the hour wheel arbor. This is attached to the jack screw through a friction clutch. There are a series of numbers 3,3,3,4 there does not seem to be any order these numbers as representing a serial number. However, the case and a number of other parts are stamped with the number 3.

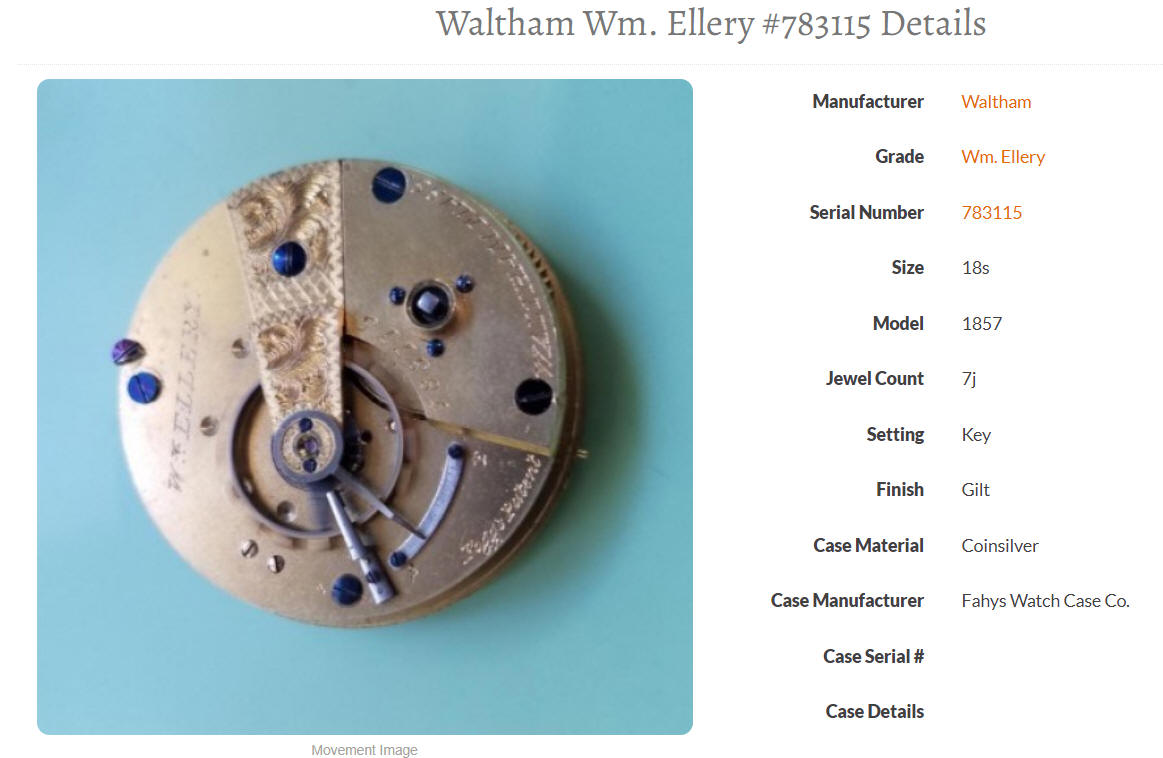

This illustration depicts the type of Waltham watch movements used in the time lock. The William Ellery model was introduced in 1861 as a cheaper version of its prior successful P.S. Bartlett. While it still commanded about two months' pay for a private in the Union Army, it was steadfast and unique when compared to the cheap Swiss watches selling within the same price category. During a time of war when over one million soldiers were in military service, this affordable watch quickly became known as "Soldier's Watch." It was in a class of its own compared to other options available to consumers at the time. At wholesale it cost $13.00, or about $25.00 at retail, still a significant amount of money, but it was the only watch near that price point that was considered reliable. By comparison, other dependable watches of the era could cost more than twice as much. ¹Waltham made about 140,000 of this model. The size 18 was Waltham's largest pocket watch movement. Of course Waltham or some other firm had to make alterations in the movement for use in this time lock. Given the amount and quality of the alterations it is likely that these were performed by Waltham. The first obvious alteration is the alteration from a key wind to a stem wind. This required the entire plate over the winding barrel to be remade. The Model 2 in the Mossman collection, see below, is missing the watch movements and was overlooked for the significance that the Overmyer and Huston time lock was. If one had pulled the patent it would have become obvious, but apparently never was. Until now it was thought that the first instance of a time lock equipped with pocket watch movements was introduced by Yale in 1888 in their series of time locks, Models a through EE. The movements were the most expensive component of a typical time lock and the E. Howard company has a virtual lock on the manufacture of those movements. An exception was Sargent and Greenleaf which from the beginning made their movements in house. Yale's was an attempt to bypass E. Howard. They were, however, a failure as the pocket watch movements were not up to the task. Yale also used Waltham movements, size 14, Hillside grade. These were a smaller size than the 18 size used in this example. The design used in this and the Model 2 example would not have been a success for several reasons. The first being that the connection between the jack screw and the watch movement was a friction fit, which after many cycles would have come loose since one has to move the jack screw backwards to reset the time lock after each use. The use of a ratchet wheel here would have solved that problem. Still there were issues with the bolt dog, not the least that tipping the safe would also tip the bolt dog to the 'off guard' position. That issue seems to have been addressed in the model 2 with a leaf spring. However, having this leaf spring means more power is needed to push the bolt dog into the off guard position at just the time that the watch drive is at its weakest point at the end of its run. It cannot be known, but this author believes that the watch movements would have not been up to the task, just as they were not in Yale's attempt. It was not until the Consolidated Time Lock Company successfully introduced their first pocket watch driven time lock in 1902 using an Elgin Watch Company pocket watch movement that this design succeeded. Three years later the firm switched to the South Bend Watch Co. movements. In 1906 Bankers Dustproof (formerly a part of Victor Safe) used an Illinois Watch movement The last firm to do this was Mosler after their buyout of bankers Dustproof in 1916 and so also used pocket watch movements by Illinois Watch Co., later Waltham and then Swiss sourced Recta movements that were made for Mosler since by this time pocket watches were no longer being produced by any firm. Mosler was the last company to use watch movements and ceased operations in 1967. Afterwards time locks all went back to the special-purpose movement designs, almost all Swiss-made and designed to be replaced periodically rather than repair and service. Specialized movements purpose-built for time locks was the norm throughout the history of the time lock. The pocket watch design always remained a small segment of the market. Nonetheless, the the Overmyer & Huston Model 1 has the distinction of being the first to try using commercially made pocket watch movements in place of special-built movements designed from scratch for use in a time lock by using a pair of altered Waltham size 18 movements. The inventors were trying to make a far less expensive product, using a simple design and bypassing the expensive special-built time lock movements, usually made by E. Howard, with commercially available pocket watch movements. It was an attempt to make a much cheaper time lock to compete on price. In 1876 the time locks available by the industry leaders Sargent & Greenleaf, Yale and New Britain Bank Lock Co.(Pillard), had quite expensive, complex as well as visually beautiful time locks. They were in the price range of $400 to $450, a great deal of money at the time; equivalent to about $10,000 today. One look at these time locks compared to the Overmyer & Huston and one can imagine it selling for half or less than the competition. There were several problems with their design and these are discussed in the video below. The time lock never went into production. There was also a model 2, but this too was never commercially produced. There is only one example known of each model, the Model 2 is in the Mossman Collection at the General Society of Tradesman and Mechanics Museum in New York City, see below. The Waltham movement source was probably the only practical and economical way to test their deign. Using E. Howard would have required an entirely unique design to fit their requirements. They designed their time lock around the cheapest source of movements available at the time, whereas a large firm such as Yale could design their model 1 from the ground up.

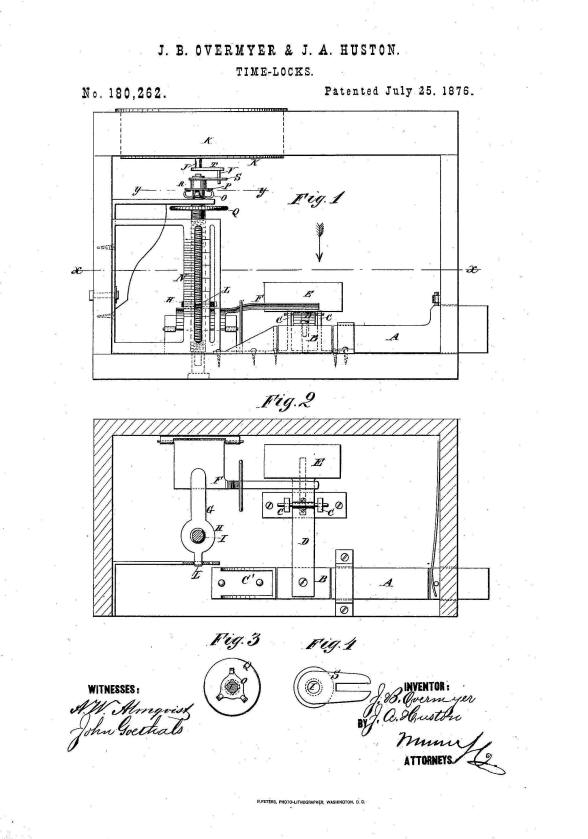

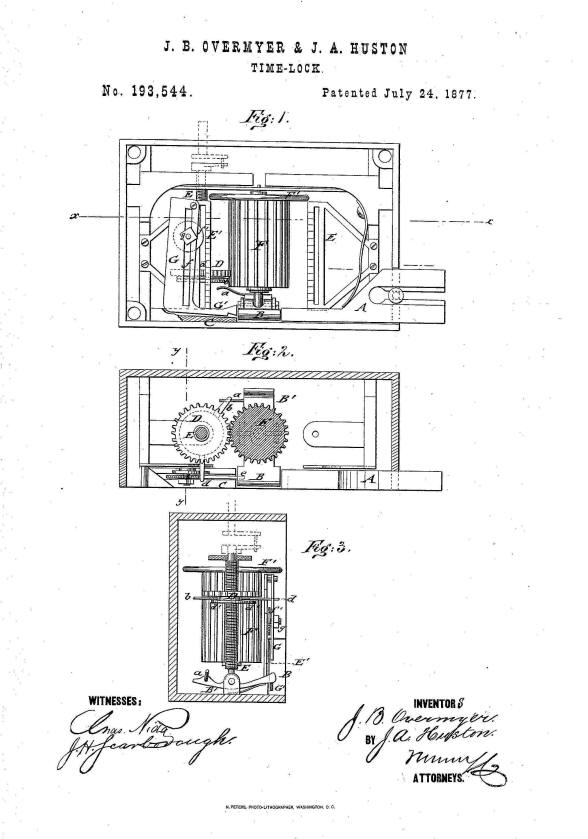

The first patent drawing is that of the Model 1 and the second the Model 2. The model 2 included a ribbed center drum, geared to the jack screw pair. In this configuration the operator only turns the center drum to adjust both timers simultaneously avoiding a mismatch as can happen in the model 1 where the operator winds each jack screw separately.

This video outlines and demonstrates the Overmyer & Huston, time lock. It was an early entrant into the rapidly expanding field of time lock makers, started by Sargent & Greenleaf with the first commercially successful time lock in 1874.

Above, two photos of the Model 2. This is the only example known and is in the Mossman Collection at the General Society of Tradesmen and Mechanics Museum in New York City. It was donated by the Consolidated Time Lock Company. At the time this was made, the company was known as the Hall Safe & Lock Lock Co. It is likely that Hall made this lock for the inventors as the case is a typical Hall design for the time. This example is missing the two Waltham movements as well as the pivoted plate that controls the timed throw off of the bolt dog. The case is in immaculate condition, either it was re-plated or this lock had never seen service. Overmyer and Huston, 1876. There are only two locks by these inventors known. One Model 1 and one Model 2. Given the lack of any information on this time lock it is assumed that these were never commercially produced. The Model 1 is the only one that has the original pocket watch movements. Given that Hall made the case and most likely the entire time lock for the inventor's Model 2 only one year later in 1877, I believe that Hall also made the Model 1. This lock has the number 3 stamped on the case as well as several components as well as the back of the Waltham movements. So likely there was more than one made. Given the serious deficiencies in the bolt dog design as described above and in the demonstration video it is doubtful that this lock was ever put into production. But there very well could have been a few prototypes made to test various functions. Case #3, movements #787094 and 794633. file 310 1. Disrupting Time, Industrial Combat, Espionage and the Downfall of a Great American Company, Aaron Stark, pp.42-43 |