|

Sargent & Greenleaf, Rochester, New York - 1874 through today. Introduction The article below relies to a great extent from information derived from American Genius, Nineteenth Century Bank Locks and Time Locks, by John and David Erroll.

The

James Sargent Lock Company was founded in 1857 by James Sargent specializing

in safe locks. In 1865, Sargent partnered with Halbert Greenleaf a former

employer to form Sargent and Greenleaf (S&G).

S&G introduced the first large-scale, commercially produced time lock in

1874 the Model 2. Their model 1 was made in limited numbers and was a

combined combination and time lock with the time lock operating directly on

the combination lock by blocking the combination lock's fence from

functioning while the time lock was on guard. Most other makers with the

exception of the Hall Safe & Lock Co. which was later reconstituted as the

Consolidated Time Lock Company performed their duties by operating on the

safe's bolt work rather than the combination lock. S&G's first stand alone

time lock, the Model 2 was introduced concurrently with the Model 1. It

contained the same two movement module as in the Model 1, but without the

combination mechanism. Instead it operated by blocking, also called

'dogging' the safe's bolt work. It was the first first utilized in 1874 on

the vault door of the First National bank of Morrison, Illinois. This was a commercial success with four

different versions introduced using the original roller bolt dogging device.

The fourth version sold between 150-200 units. In 1877 S&G introduced a

major innovation in their bolt dogging design called the "cello bolt"

because of the resemblance to that instrument. Later the term 'drop bolt'

took hold because the redesign of that part in 1877 with the introduction of

their Model 3 time lock ended the visual similarity but the part still, as

before, dropped to the bottom of the case when the time lock went off guard.

Altogether from 1874 through 1927 the model 2 went through fifteen design

revisions, all of them, other than the introduction of the cello bolt ,

minor in nature. Production numbers are unknown but must have gone into the

many hundreds to perhaps a thousand. A couple of hundred or so of the Model

2 survive. One must remember that this was before the time of effective alarm systems let alone central automatic alarm systems electronically connected to law enforcement and this was especially true in the smaller towns. The safe was all there was between the robber and the contents, except of course, the person who had the combination. The time lock concept proved to be immensely popular and profitable. The people the time lock protected were generally wealthy and could afford the large margins enjoyed by the time lock manufacturers. For example in 1874 S&G charged about $400 for their Model 2 time lock. When Yale introduced in 1875 their Model 1 it too was about $400 and $450 with their optional Sunday Attachment™ which was introduced in 1878. No information is available for the wholesale cost of S&G movements since they were made in-house, but a Yale Model 1 wholesale and when delivered by the E. Howard Watch Company in 1885 was $50.00. This is a 9 times or 900% markup! Just to put this into perspective $450 in 1874 is worth approximately $9,000 in 2016. The price of a time lock could cost as much as the entire safe into which it was installed. This gives the reader the great value that the owners gave to this new technological innovation.

But this is not the only reason. Yale Lock Manufacturing Co. was their largest competitor and in 1877 these two companies colluded to dominate the market. This was many years before the concerns with corporate domination and price fixing through collusion and trusts resulted in the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890. To drive home the point, above is a reproduction of a joint catalog released by S&G and Yale in 1883. They readily show their wares side by side and, not coincidentally, the pricing is identical for time locks that would otherwise be in competition! Look carefully at the illustration of the Yale No. 1, it is upside-down, reminiscent of the famous postage stamp the 'Inverted Jenny'. One can easily see how the catalog printer mistakenly looked at the S&G illustration seeing the two dials at the top and then applied the same thinking to the Yale time lock. The catalog has an insert showing the corrected depiction.

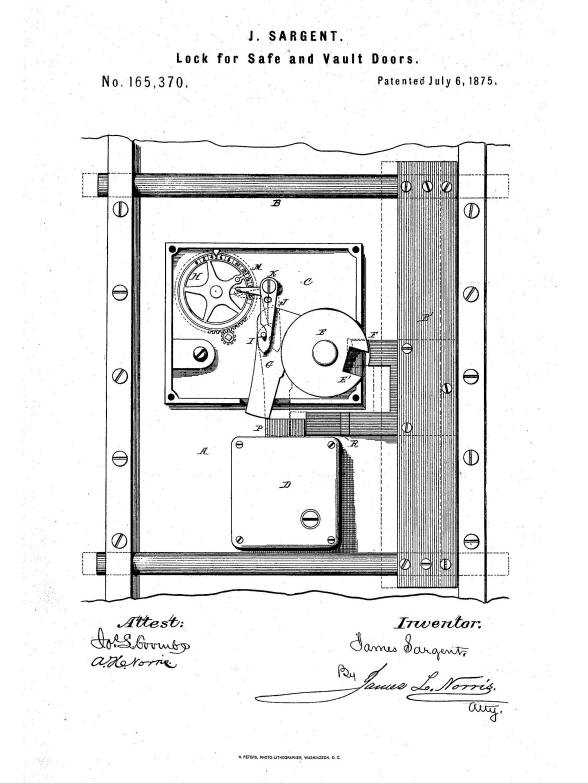

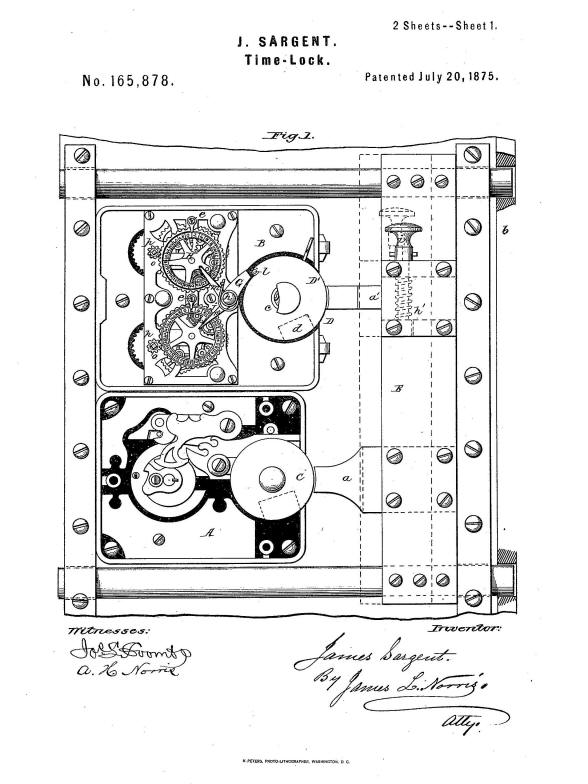

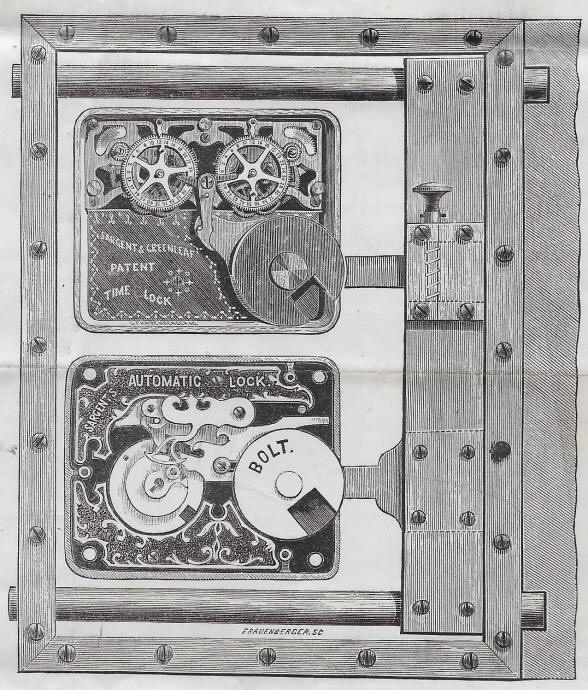

The first patent drawing is the earliest I have found for a S&G time lock. Here one can see the development of the rollerbolt and drop lever. Notice the additional piece that protrudes through the bottom of the case and prevents the rollerbolt from rotating into the off guard position as long as the correct combination has not been dialed in, this 'dual custody' feature was never incorporated into any future S&G time lock. The second drawing is from a patent dated July 20, 1875 and shows a dual movement time lock of a very different configuration with the rollerbolt directly in the middle and below the two movements instead of off to the right, than that which was produced. This model used a spring loaded rollerbolt rather than relying on gravity for the bolt's rotation. No example of this time has been seen.

This illustration is from December 16, 1875. It shows nearly how the production Model #2 time lock looked mounted to the safe door. Notice the use of the rollerbolt in both the combination and time locks. Clearly Sargent used the same design from his combination lock for use in the time lock. However, while both were used to dog the boltwork, the rollerbolt as used in the combination lock was to isolate the wheel pack from the lateral pressure of the door bolt , ensuring that the bolt handle cannot be used to pressure the tumblers and give away their position. There were no tumblers in the time lock. When both were simultaneously aligned with the door boltwork, the bolt could be moved into the two recesses and the safe door opened. A comment from this author on the illustration of the time lock. The extensive skeletonizing of the front movement plate has been illustrated in some of the company's advertisements, but this style has never been observed in fact. This extensive fretting of the plate would make it more prone to violence of percussion or explosion and the first few production models did have some cutout design around the central section and under the two dials which was replaced a few years later with a solid plate for these reasons. Also both the time lock and combination lock are shown the same size, but the model 2 time lock was about one-half inch larger in both height and width. Below I will explore the various design features and other information that would be interesting from a collector's perspective. S&G 1874 and the present day:

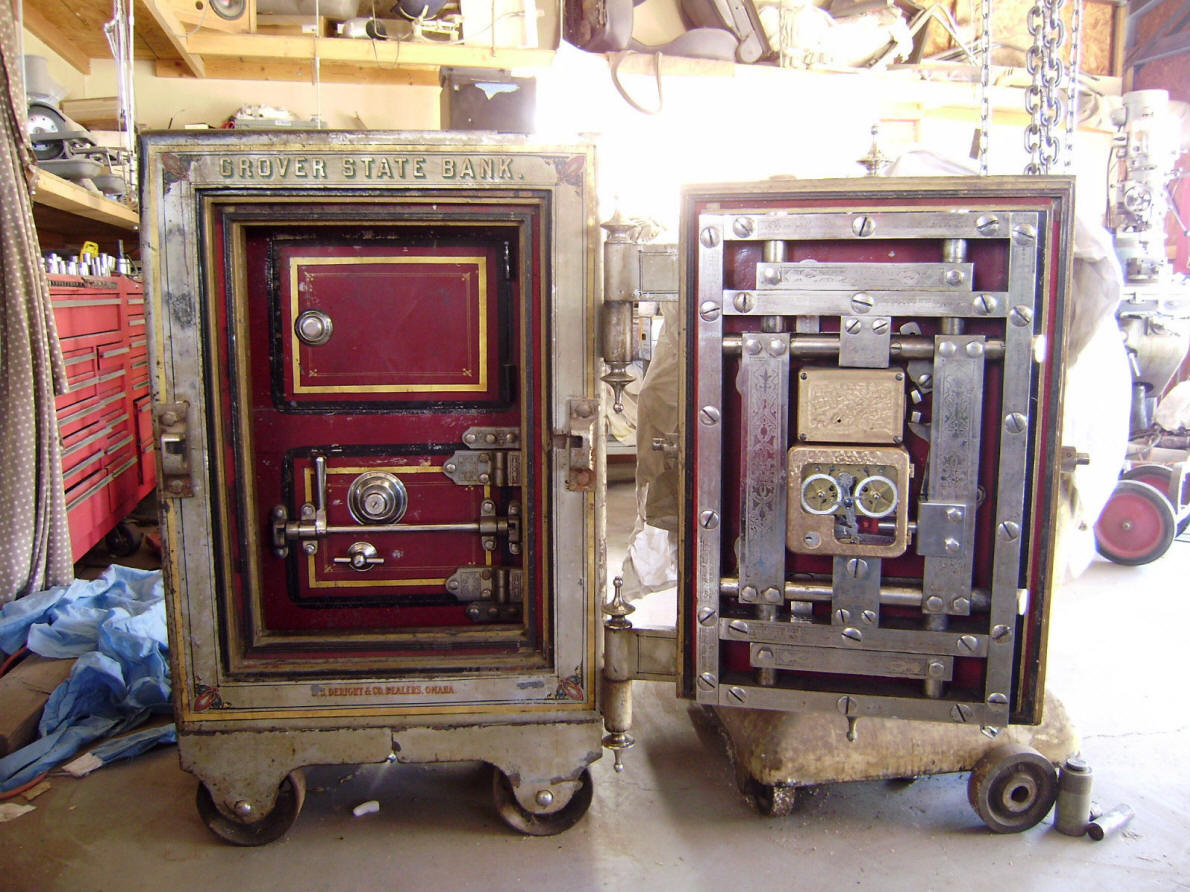

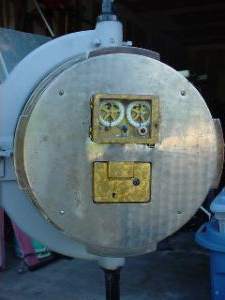

These two photos show the earliest known example of S&G's Model 2 version 1, 1874, case and movement #40 and a contemporary offering, Model 6370. S&G is the only surviving maker from the beginning of the time lock industry. Below I will go through some of the characteristics of the S&G line of time locks and their changes through time. The first to be considered are the early models. Model 1 was made in so few numbers that it will not be shown. It should be noted that the Model 1, 2, 3 and 4, were all introduced between 1874 and 1878 and so the evolution in case, movement and bolt decoration ran fairly concurrently across these models. Production of the Model 2 through Model 4 continued until 1929 when the great Depression brought all new bank building and business in general and thus the demand for time locks of all models to a halt. Case decoration:

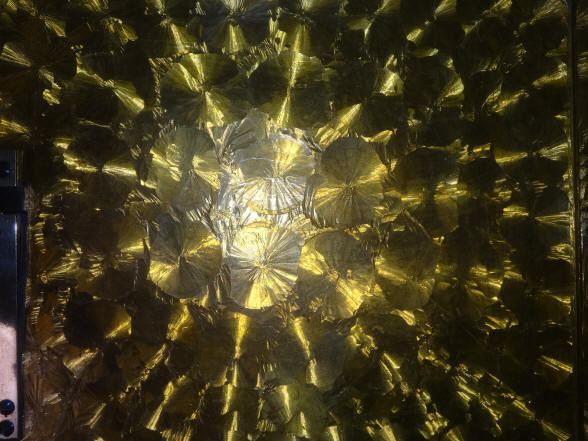

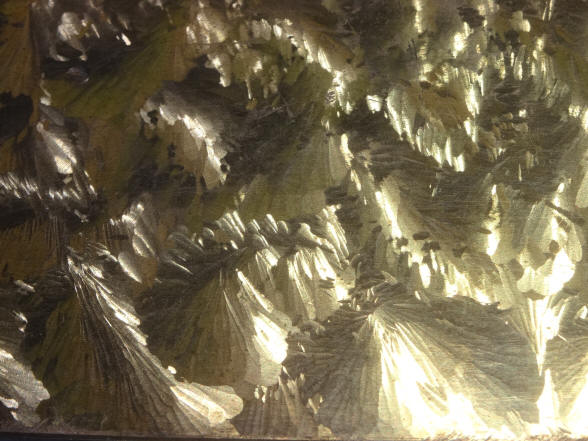

The first photo is a Model 3, c.1881 and next a Model 4, c.1888 each a solid door version of their time locks having what is called a 'coin vault' door. This style was used in safes where a coin bag could otherwise smash the glass of a time lock when the door was accidentally closed against the coin bag. Displayed are the two styles of decoration S&G used on the surface of their early cases, prior to 1910 and generally ending by 1924 when this style became available only by special order. The repeating 'spotted pattern' on the left is their more common design. The second is the 'crystalline' style and is also displayed on the example of the Model 2 above. However, the surface is actually much more complex than what is normally referred to as damascene. In the 18th century through today a damascene is pattern applied through a milling process into a smooth surface to create a repeating pattern.

These photos show a close up of both patterns. In the first, one can see S&G produced their surface design through the pattern being raised from the surface. Also it's easy to see that even in the repeating spotted pattern the spots are not identical as would be expected with a conventional rotating tool being used to create a repeated pattern on the surface of the metal. The second shows the feathering pattern which looks a lot like the type of crystalline growth one would see from moisture freezing on a window during a cold winter day. This pattern too is raised from the surface and so is referred to as jewelling rather than damascene. Afterward the case was plated in gold. The gold plating became an up-charge option by the late 1880's But the jeweled surface continued until around 1924 when other finishes, most notably the satin nickel finish, began to replace the jeweled case and accelerated after WWI when it was discontinued with the gaining popularity of art-deco in safe design. This author has not yet been able to discover how S&G made this jewelling. After 1924 all cases were offered in the satin nickel finish, see below under movement and case sizes. There also was a custom option for a satin bronze finish but these were never popular and few were made. It seems that few of the Model 2 through Model 4 were made in these other finishes. Back plate and drop bolt decoration:

Both photos are examples of the Model 4. c.1887 and a later production issue from around the 1920's. Note the total lack of decoration on the snubber lever, dog and drop bolt by this time. When the Model 4 was introduced in 1878 the engraved ivy leaf design on the top movement plate had already been discontinued, however a few of the first Model 3's introduced in 1877 did have this feature. The first example shown here has case #1690 and movement #1685, the second, case #3465 and movement #4933, the movement probably a later replacement. The elimination of decoration appears to have been gradual with the ivy pattern eliminated first and then the logo plaque from both the drop bolt and back decorative plates.

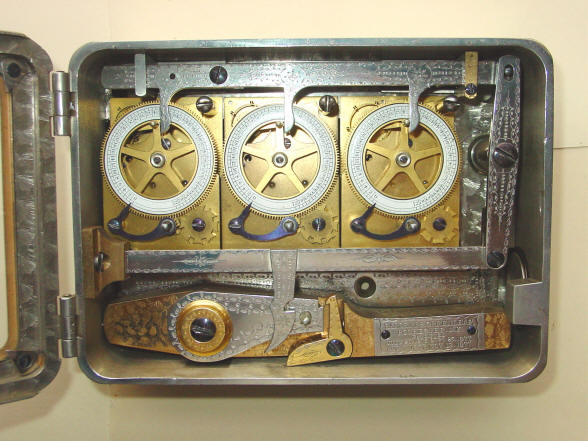

Another example of early and later snubber bar, drop bolt and rear plate design work. The first seems to have been purposely made to bring visual interest. Here we have brass movements mounted in a satin case with full decorative snubber bar and bi-colored drop bolts on a Model Triple B v.2, case #84, movements #663, #664, #665. If one looks carefully the case interior door still retains the original jewelling. What we have here is a customer who wanted to 'update' his case from a gold jeweled case to a satin finish. The case number and movement numbers are surely OEM. The movements are consecutive and early as is the case number and so was surely made with the original gold jeweled case. Unlike the earlier time locks with integrated movements it is impossible for the case and movement numbers to not diverge as time went on since the case had one number for every three movement numbers. Also these movements were being used across the S&G line for automatics and later four movement time locks. So the number of movements far outstripped any serial number on the case as time went on. When one sees an S&G lock of any model that has a case and movement set that is somewhat close in number, it is an early example of that model's run. As time went on and with the introduction of four movements locks, the divergence of the serial number in say a Model O that had 'L' sized movements that had been used in the Model Triple A, B, and C for a number of years cannot be close. Here one must look to the consecutive numbering of the movements to ascertain originality. The second photo shows a much later example of the Triple B v.3 with 120 hour movements dating this to the later 1920's. Note the complete lack of engraved decoration. Movement plate decoration:

The very earliest Model 2 and 3 movements had decorative ivy leaf engraving on the movement top plate and dial wheel arms. This was only done by the firm for the first three years of production. There may be a dozen examples of the engraved front plate design extant. The second photo shows the same movement plate without decoration. The first photo is a Model 2 v.1, 1874, the second a Model 2 v.4., 1876 Both still retain the fully skeletonized top plate showing the wheel work and escapement. This changed by Model 2 v.11 in 1886 to resist derangement from explosion. Also the dials themselves began to be secured by screws rather than fixed to their arbors making maintenance and adjustment easier. S&G switched from the black background dial format to white in 1877. Note the dial on the left has 48 hours with the one on the right has 46. The very first few time locks produced by S&G in 1874 had dials to 48 hours. However after these were made it was discovered that the movements did not have enough power in the springs to go for the full 48 hours. So S&G sent a circular to the few Banks that had already installed the time lock warning them to only wind the movement up to 46 hours. The movements that had already been made had their dials swapped out to the 46 duration format before sale and for those that were already installed, S&G would as a part of their routine annual maintenance swap out the 48 dials for the 46 hour dial. Therefore, very few time locks were left with the original 48 dials This difference is what makes this a Model 2 v.1. Two examples are known. S&G never did introduce a 48 dial in their Model 2, but did introduce a 66 hour version in 1878 to compete with Yale's optional Sunday Attachment ™. By 1886 the 72 hour duration became the industry standard and a 72 hour version of the Model 2 was introduced that year. This is another marker one can use to estimate age of a movement. However, there were some infrequent cases where a lock was returned to the factory to be retrofitted with longer duration movements. Sometimes this was done within the original movement plate and so the numbers may match up between movement and case but are too early to have been made when the up dated features first appeared. In other cases the movements were swapped out and here the mismatched case and movement numbers will be obvious.Movement design, Integrated movements:

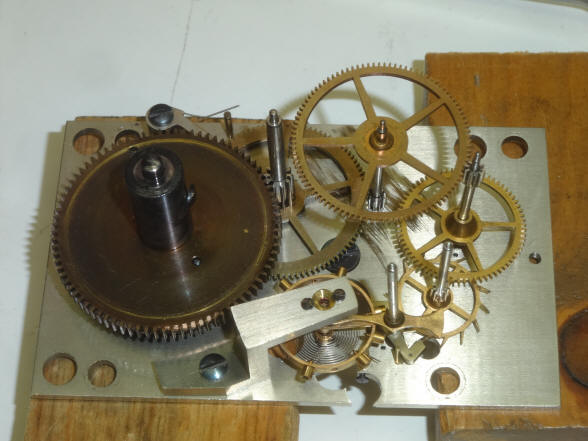

Model 2 movement. Both movements are integrated into to a single front and rear movement plate requiring disassembly of both movements even if only one was malfunctioning. Model 3A and Model 4. In the Model 3A, left, one sees the continuation of the single movement plate for both movements. This example was the Model 3 adapted for use with automatic bolt motors, so the drop bolt below is replaced with the drop lever dog serving to trigger the bolt motor. In 1878 S&G introduced the Model 4, right, and here we see a split front plate for the time lock movement. The rear plate is still a single plate, but at least this allows for the servicing of one movement at a time. This is the beginnings of designs toward easier maintenance allowing for each movement to be independently disassembled. It still does not allow for interchangeability. It is interesting to note that even after the introduction of the modular movement in their three movement model Triple A in the S&G line in 1888, the company never saw the need to have a two movement modular model. They only applied that design to their three and four movement time locks. Whereas all of the other makers eventually did introduce a two movement modular design. The split front movement plate / solid rear plate design was not a new innovation. An example in 1665 by the British clockmaker Johannes Fromanteel, used the split plate design to allow removal of either the time or strike train separately; there are surely earlier examples. The early entrants into the industry, S&G and Yale immediately saw the need for redundancy in their time locks. There were two independent movements of which only one was needed to put the lock off guard and allow the owner to dial in the combination to open the safe. Hall and later Consolidated was the exception with their single movement offerings where they had elaborate override systems to compensate for the obvious problem of a lockout from a single movement. They attempted to gain market share by offering a less expensive alternative with only one movement vs. the two offered by S&G and Yale. This was met with limited success . However all makers who had two redundant movements (and only two were offered at this time) fabricated these upon a single movement plate. So if one movement was malfunctioning, the entire mechanism containing both movements had to be removed for servicing leaving the owner unprotected. My guess is that this was a rare event. Probably a normal clean and servicing would be performed 'on the spot' by the service tech. This would require that the tech be a professionally trained person with all the equipment on site to do the job. I have done this work, and it is not easy to do a complete overhaul of a time lock mechanism even at my bench where I have all the comforts of home let alone in a satellite location. If there was a major problem like a cracked jewel or if the tech made an error causing the balance wheel hairspring to be deformed by mishandling, the owner would be left unprotected since at this time there was no ability to interchange these combined movements between locks. The advent of the Model 4 allowed a limited ability for the owner to continue protection while one movement was being serviced. However, my guess is rarely was this necessary. The tech was able to service the movements in a timely fashion. Remember the incredible fees charged for this service so one would expect that the time lock would be serviced and put into running condition on the spot, (see A Brief History to the Time Lock Industry in this web site). By the mid 1890's the entire mechanism containing the pair of movements could be swapped out and if one sees a case serial number with a very large difference between it and the movement number on the Model 2, 3, or 4, then one can assume the movement was swapped out at some point. Dial designations:

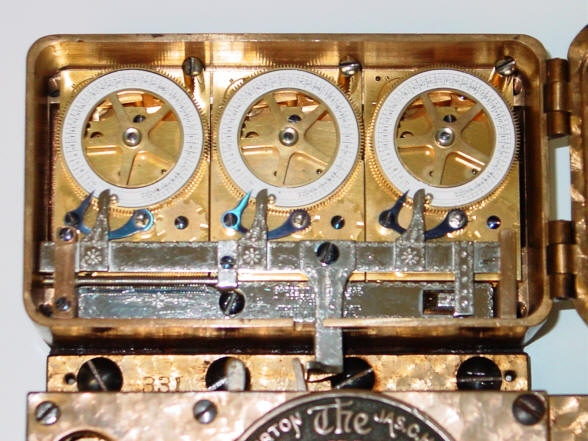

This Triple C has all three types of dial inscriptions on the M-movements. Prior to 1896 there was no attribution. In 1896 the dials displayed "Sargent & Greenleaf Company" and this was changed in 1918 to "Sargent & Greenleaf, Inc." after its reorganization into a stock company, on the right. These markers are helpful in identifying proximate ages. The serial numbers of the movements follow this with increasing values as time went by, #208, #720 and #1548. The M-movement was produced until 1953. Introduction of modular movements:

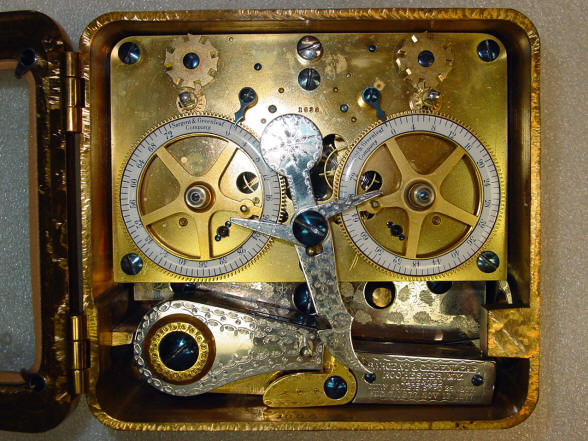

S&G also first popularized the modular movement. This photo shows a very early S&G Triple A, case #46 and movements with S&G 'L' sized movements #199, #200, #201, made in 1889 making this the earliest Triple A known. Again they were not the first, Amos Holbrook did this in 1858, and Yale introduced modular movements in the form of separate Waltham watch movements in their Type B movement introduced in 1888. However the former made only a handful of time locks and so had no impact on the trajectory of the design in the market and in Yale's design it was very difficult to actually remove and replace the movements and required a major disassembly of the lock to accomplish this. S&G introduced the first easily individually removable movements in their Model Triple A, B, and C in 1889. At this time the movements were still not fully interchangeable, they still had to be replaced in the same order they were removed. If the maintenance person saw a movement that needed attention it would be removed for off-site service and the remaining two employed to keep the lock functioning. A slightly greater risk of lockout but still not by much. True interchangeability where a technician could simply arrive with a movement of the same model as the malfunctioning one and could do a simple swap out did not happen until 1895. Why this took so long is a mystery to me since the advantages are obvious and there seems to be no real technical reasons to prevent this. No longer would a customer have to be with a lesser dependable time lock while the movement was serviced. Still it was a huge improvement over the earlier integrated movements. Note the construction of the snubber bar here and in the photo below the earliest examples had separate dial lever pieces attached to the horizontal slide bar. This was quickly changed to a single piece to avoid the possibility of the dial levers breaking off in the case of explosion leading to a lockout. Less than five examples are known to have this pre-integrated design.

The first photo shows the earliest modular but not yet interchangeable movements in the Triple A from 1889 and next a later Model O quad movement (later denoted 6403) from c. 1910 with fully interchangeable movements. The Triple A operates on an automatic bolt motor, in this case a Burton Harris. Automatic systems eliminated the need for manually operated bolt works, the handle that one would crank after the correct combination was dialed in. The advantage to this design was the fact that one less opening, and thereby way for a safe cracker to enter, was eliminated from the door. The disadvantage is expense and further complexity and the fact that the bolts had to be pretty violently shot open and closed. If there is some problems with friction from corrosion or other issue, one can feel the resistance when manually operating the bolt work. But with the automatic, the powerful springs take over and if the jam is bad enough, the bolt motor may not be able to withdraw the bolts. Like any consumer product, safe design went through different styles and popularities. Manual bolt work was the first type available. Automatics gained popularity in the 1880's with the rise of the time lock, without which the automatic system could not operate. After the 1920's the automatic began to fall out of favor and the manual bolt work became dominant again. The second photo shows a the bolt dogging work below the four movements and this was used on manually bolt actuated safes. The original cello bolt shape has morphed into a long shape, but the principal remains the same. Larger safes and especially walk in vaults used manually operated bolt work as the size and number of bolts precluded the use of a spring operated device to move them. There was a report issued to the Secretary of the Treasury titled Improving Vault Facilities of the Treasury Department, and circulated to the 53rd Congress in 1893. It makes for fascinating reading where in text and numerous photos many of the popular models of safes of the day were systematically broken into. Nitroglycerine could be used upon the seam of a door jamb so no hole need be in the door whatsoever. The most interesting is a manual drilling device that could cut a 4" hole through the side of a safe in less than two hours! These are tools only the most sophisticated burglar would have, but it proves the fact that no safe is "safe"! At this juncture there needs to be some clarification about what exactly interchangeability meant in the 19th century. Interchangeability of the individual movements did not extend to the individual components of the time lock mechanism and especially the components within the movements themselves. The term interchangeable tends to imply the ability to assemble a mechanism typewriter, watch, clock or firearm, from a supply of parts chosen at random. In fact, every nineteenth-century manufacturer of complex mechanisms designed those mechanisms to be adjusted at the time of assembly. Thus the interchangeable parts were interchangeable but only to the degree necessary; the degree of interchangeability was stipulated by the design of the product. The proof of this is the fact that nearly all time lock makers use consistent numbering systems for their components. For example a case may be stamped 393 and if so then the door, drop bolt and snubber bar assemblies will also be marked with the same number. Movements were also individually numbered and the numbering was consistent through the escapement assemblies, i.e., the balance wheel, balance cock, and lever escapement. This numbering system was followed by S&G until they stopped making their movements in-house and subcontracted their product to foreign manufacture in the 1950's. S&G was nearly unique in the industry in making their entire time lock, including the movements in house. Because of this the case numbering and movement numbers, especially early on in each of the model production runs were closely related. Multi movement locks would be consecutively numbered. Because of this it is easier for the collector to ascertain originality of the entire S&G lock than it is in many other companies. Proof of full interchangeability with respect to the movements is the fact that most time locks seen in the collector's market today do not have consecutive serial numbers as they have had their movements swapped out during their time of service. the Model O above has a potpourri of serial numbers for the 'L' sized movements #15054, #10615, #12171, #13175. This indicates that this time lock has a long service life to have had so many movements changed out spanning nearly 2000 serial numbers. Consecutive numbers are always more desirable and usually indicate a lock that was in service a much shorter period of time. Drop bolt design:

These two examples show the first roller bolt design, left and the improved

cello bolt, right. Both are in the off guard positions where the safe's bolt

work could slide into the recess afforded by the round bolt and the area

above the cello bolt. The roller bolt, left, needed a special adaptor to

operate Notice the use of the red paint color on the inside of the first

case. S&G was not the first to do this. It appears the color which gained

the name 'Security Red' appeared as the inside case color of choice on many

lock makers for their better, more expensive products and is seen at least

as early as 1833 by many makers, long before the introduction of the time

lock. S&G too used this on their combination lock cases as did Hall. For the

S&G Models #1, #2 and #3 time locks it appeared until 1877 or 1788, so they

were available only a couple of years and made in limited numbers with the

original paint. Many cases lost their paint as it was rather fragile and

easily removed during any restoration process. It is unknown if Model #4

ever had this applied; this author has not seen any. Holms also used the

color for their time locks. Model #2 v.2, 1874, case and movement #129.

Right photo, Model #2, v.11, c.1886, case #1087, movement #1094.

This example has

the improved bolt with its two step articulated design and could function on

a simple, straight bolt through the hole in the side of the time lock case,

see video demo below, this was introduced, in 1877 in version 6. It was

known as 'cello bolt' for its obvious resemblance to the instrument and was

one of S&G's most important contributions to time lock design.

By this time production had reached higher levels and the movement and case

numbers may not have been identical coming from the factory, but in this

instance close enough to assume the case and movement are original to each

other. The ivy and leaf engraving on the front movement plate and dial

spokes disappeared after version two in 1877. The plaque on the cello bolt

has inscribed “Sargent & Greenleaf, Rochester, N.Y. Patented July 20, 1875,

Aug. 2, 1877, Sept. Sept. 7, 1877 Nov. 13, 1877." These patent dates would

begin to appear in 1877 on many of their products. This coincides with the

accelerated patent litigation S&G and Yale engaged in with their

competition. The company began using white dials on their product line in

1878. Notice the skeletonizing of the movement plate under the dial work in

the earlier lock. By version 11 in 1886 the plates lost most of the cutout

perhaps a nod towards making the movement more resistant to explosion.

In 1877 S&G introduced the Model 3. The low profile drop bolt was introduced and lost its similarity in look to the cello. This allowed the lock to fit into a greater number of safes with tighter bolt works. This version with slight modifications would be the bolt design for the entire S&G line that used a drop bolt until well after WWII. The early models still had the ivy leaf engraving on the top plate and are quite rare as 1877 was the last year this was done. Also the drop bolt was not nickel plated. This lock from 1877, Case and movement #11 making this the earliest known example and also has the 'Security Red' painted interior. The second example is c. 1887. The drop bolt now has the nickel plating and attached plaque with the company name and the four patent dates, c. 1889, case #1306, movement #1286.

In July of 1878 S&G introduced their Model 4 a two-movement time lock that was smaller than their model 3 and even easier to fit into smaller safes. The drop bolt was tucked a bit behind the from movement plate which is a bit more obvious in the first photo due to the perspective of the photo shot. The model 4 was the first to employ Geneva stops as well as the simplified door lock using a handcuff type key. Version 1 and 2 departed from the wagon wheel style and used a solid dial. By 1889 S&G went back to their standard dial style. The solid dial would return in their smallest movement, the size 'H' sometime in the early 1900's. The Model four never had an engraved top movement plate nor black dials since both of these features had been discontinued the year before. Left, Model 4 v.1, 1878, case and movement #227. Right, Model 4 v.3, later 1890's. The dials have the post 1896 company attribution.

The triple A, B and C were introduced concurrently in 1889. The first photo shows the earliest example known of the Triple B v.1, case 38, movements #256, #257, #258. Photo right, after 1924 the satin nickel case became the standard style. All attempts at component decoration had by this time been abandoned, though the basic design, with minor alterations remained the same. The design of S&G's drop bolt design was a key to their success. It was what distinguished their products from all the others. No other time lock maker made as simple and fool-proof a bolt dogging system. It relied on the simplicity of gravity for its operation. Of course it was bolstered by the patent litigation and market collusion with Yale. But still it was an ingenious device. The video below illustrates the operation.

Movement types: The examples illustrated below are all from between 1910 and 1929. By this time true interchangeability was achieved and most cases and movements were the satin nickel finish.

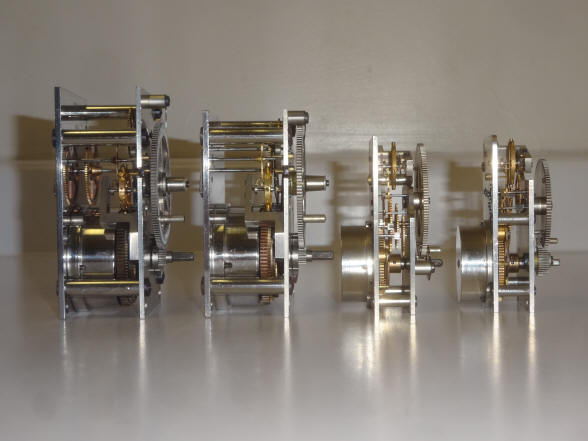

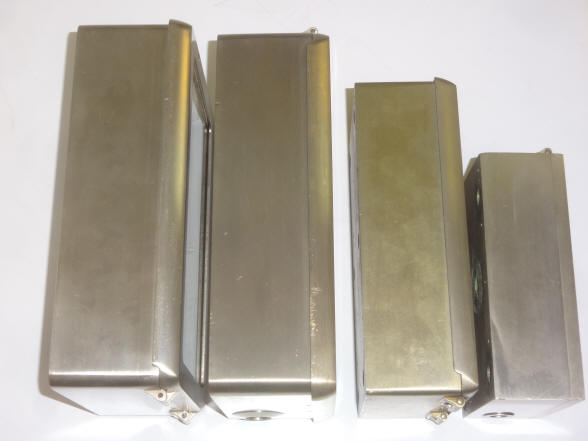

During this period S&G employed four different sized movements. These were designated from the left as, 'R', 'M', 'L' and 'H'. The largest movement has a 96 hour duration while the remaining three have S&G's standard 72 hour duration. The "R" movement only came in the 96 hour duration while the other three could be had in72, 96 and in rarer instances 120 hour durations. The 120 hour durations did not come along until the late 1920's. By 1886 the 72 hour duration was standard and by the 1920's most of their models were available in the optional 96 and a few years later 120 hour durations.

The customer paid dearly for the option. Shown above is an original price list from April 22, 1929 just before the stock market crash that preceded the Great Depression which brought a halt to industry wide time lock sales until after WWII. The triple B with standard 72 hour duration was $311.10, with 96 hour duration $355.54 and with 120 hour duration $477.77. So the extended 120 hour duration option cost the consumer an additional 53.6% over the standard 72 hour duration! Also take a look at the prices, it almost seems like the company liked funny numbers. Remember at the beginning of this article that the Model 2 in 1874 cost $400.00, the triple A introduced in 1888 was priced the same, so one can see how the breaking of the S&G and Yale patent cartel and as the patents themselves began to lapse, competition began to bring prices down by 1929. S&G time locks with the expensive 120 hour duration are therefore far less common and thus more collectible. The same rule applies for the longer duration time locks offered by other makers.

All of the movements had the same wheel work configurations containing six wheels and a standard in line lever escapement with a solid brass, uncompensated balance wheel, see diagram below. One of the great advantages of this type of escapement for use in bank and safe time locks is that it is self-starting. Most time locks are designed to wind down to zero and stop when the time lock is put off guard. It would be impossible to 'jiggle' or twist the time lock around to get the balance wheel moving as is common in chronometer escapements. Try doing that with a time lock mounted onto a 20 ton vault door! This author has worked on all of movements represented here and has found them to be purposefully designed to allow for easy maintenance. Access areas and holes are drilled in appropriate locations to allow the servicer to easily remove the entire escapement without parting the plates. Lubrication points have easy access. In fact the movements are so easy to service that a semi-skilled watchmaker could do a compete servicing as opposed to the need for a skilled watchmaker needed for other time lock makers. Many of those makers used E. Howard and later Seth Thomas movements that were of higher quality or actual pocket watch movements by Waltham, Illinois Watch Co. or South Bend Watch Co. all of which require a greater skill set. This makes sense since S&G was one of the few makers that made their own movements in house rather than subcontracting to an established watch firm. Some features were of lesser quality such as the substitution of a steel stud for the customary roller jewel pin and use of a solid brass balance wheel rather than a split bi-metallic balance wheel favored in the watch industry. But in this case it was completely unnecessary. A bi-metallic balance is needed for temperature compensation errors. Unlike a watch worn on the wrist or in a pocket and is subject to wide temperature variations, a time lock is located in one place indoors and attached to a massive steel door that acts as its own steady temperature control.

Miscellaneous:

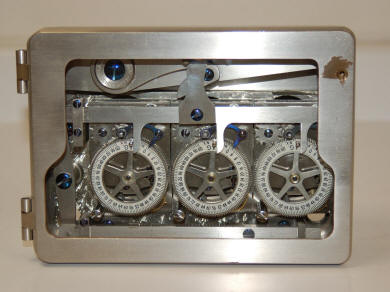

The case sizes followed the movement size. All of these have a drop bolt for use with manual bolt work. A shorter height profile case was available for all types of time locks that were used with automatic bolt actuators. Those systems eliminated the drop bolt and the space needed below the time locks for it. Notice the smallest lock in both photos has a door that is flush with the case. It appears that S&G used this type of door only with the locks equipped with their smallest 'H' style movement. All of their other cases had a door with an overlapping lip on three sides, excluding the hinge side where it was not possible. To the best of my knowledge S&G was the only maker to have this type of door. Most other makers had flush mounted doors and a few like Hall and later Consolidated had countersunk doors. All S&G locks that were designed with drop bolts had a solid glass insert. This is because the operator had to open the door to manually set the drop bolt, (see video under drop bolt section) and so there was no point to having the winding operation through a closed door via eyelet inserts through the glass. Time locks that operated an automatic bolt actuating device did not require the door to be opened to set the lock on guard. In this case the glass had eyelet holes to allow the operator to wind the movements without opening the door. With this in mind it is a convenient way to know if the glass has been replaced: if it's meant to operate an automatic, in that there was no drop bolt within the case, it had eyelets. Often the glass got broken at some point from the winding process and it was replaced with a single piece of glass and the eyelets were lost. Yale got around this problem by supplying a split glass door with the winding holes within the lower half of the door which was metal, the upper half a solid piece of glass. But S&G could not do this because their drop bolt design required the operator to see the position of the bolt and manually actuate it. Yale's design had their boltwork behind the movement plate and did not need any manual activation. Only one rare pre WWII model, an early Triple C, to the best of my knowledge in the S&G line used this split glass window design and this was also one that did not have a drop bolt. The fact that the S&G line needed a full glass door makes these particularly attractive to the collector as more of the mechanism is visible. The only other exception is their 6370 a contemporary import. These examples are all of one type of case finish, satin nickel, which was introduced in the 1920's and became standard in 1924 and coinciding with the rise of art deco which favored a sleek, simple vault door design in contrast to the earlier and much more highly decorative vault designs that employed the gold jeweled case motif. Brushed bronze was also available, but appears to have been far less popular.

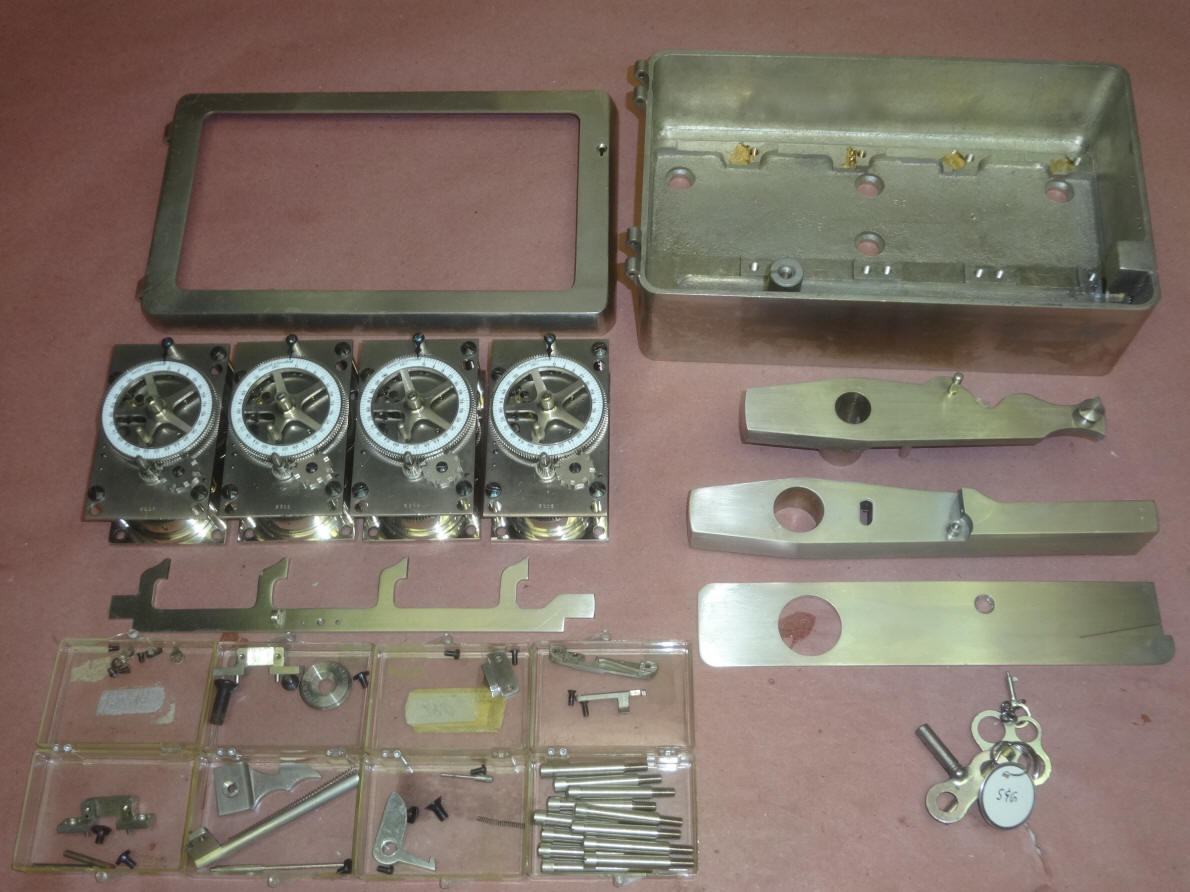

Shown here are all of the parts contained within a S&G quad M 96 hour duration lock using the largest 'R' sized movements. Any quad would contain a similar number of parts. Outside of the numerous components contained within the four time lock movements and the screw bolts used to secure them, there really are not that many parts. This is a virtue for a mechanism that must be absolutely reliable.

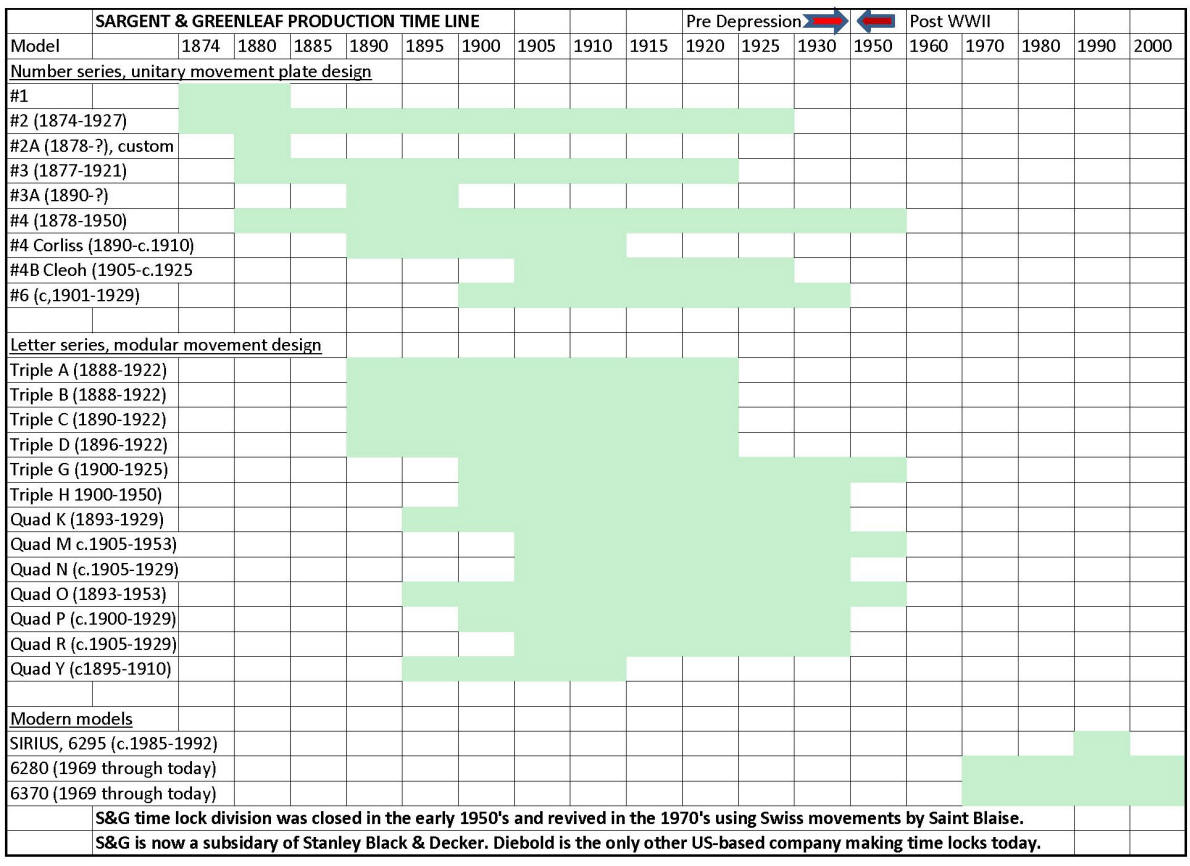

This graphic illustrates the individual S&G models in terms of when these models were in production. Time lock production at S&G as well as the other time lock makers Yale, Consolidated, Diebold and Mosler virtually ceased at the beginning of the Great Depression. Production did not resume until a few years after the close of WWII. Consolidated did not survive; Yale ceased time lock production in the US by the1950's, but contined two models imported from Switzerland beginning in the 1960's to the 1980's, and Mosler ceased time lock production in the 1980's, leaving S&G and Diebold today. Below is an overview of the time locks offered by Sargent & Greenleaf from its inception through today. Only the major models are listed as S&G had many permutations as far as case finish and movement size for any of their models in their product line. They also did quite a bit of custom and special orders as did many of the other manufacturers. Their 1927 catalog listed twelve different styles in eighteen different sizes. S&G tended to assign their letter designations according to the size of the case. This why even though the Model 4 and the Model 4 for the Corliss look so different, they both share the same case configuration. Notice as the numbers increase the case size decreases. The sizes were reduced as time went on. All of S&G's number designation time locks were introduced between 1874 and 1878 and so all had been housed in the company's signature jeweled cases. These remained the predominate case style until about 1920 when the safe and vault styles began to change toward the sleeker art-deco style of satin nickel. While the model 2, 3, and 4 were illustrated in a 1927 catalog and advertised as offered as standard in the satin nickel case finish, this author has never seen these in that finish as an OEM from the company.

Model 2, 1874. ▲ Model 3 later 1880's. ▲ Model 3A for use on automatics, c. 1891.

Model 4 v.3. ▲ Model 4 for Corliss safes. Installed as a pair. ▲ Model 4B aka Cleoh for use on combination locks.

Model 6, the smallest time lock S&G ever made. ▲ Model 2A. This is is a special order, perhaps a one off redesigned to operate directly on the combination lock fence. I include this to illustrate how the time lock makers in the early part of time lock manufacture before 1900 were willing to make special orders. Partly this was because the margins were so great that it was worth the effort. S&G did this more than most other makers since they manufactured the entire time lock in-house while most if not nearly all others subcontracted out at least the movements if not the entire lock.Below are the time locks S&G introduced with modular movements beginning in 1888. They originally had letter designations, later changed in 1922 to a four digit number. These had production runs that went well past 1910 when case styles began to change to the satin nickel finish. For uniformity, I have only included examples from pre-1900 and as such all have the S&G gold toned jewel case, excepting the Model M and N. As with S&G's number designated locks the letter designations tend to follow locks with smaller foot prints as the lettering goes on. Of course one has to account for the fact that a time lock for use with an automatic will always have a smaller height than one for use with manual bolt work because the latter has to have the drop bolt assembly below the movements. So if one just uses the width as a guide, the rule holds true for the letters A through R. The Model M and N were introduced after 1910 and so break this pattern.

Model Triple A., for use with automatics. ▲ Model Triple B. ▲ Model Triple B Special (The Upside down movement)

Model Triple C., with side pull for use in Damon Safe Co. products. ▲ Model D. ▲ Model H., the smallest three movement for use with manual bolt work.

Model K., for use with automatics. ▲ Model O. ▲ Model P, with side pull.

Model R., the smallest four movement for use with manual bolt work ▲ .Model M. ▲ Model M, special order.The model M and Model N and their special order variants were late model entries into the S&G line. These were created for the largest vaults that were being installed between 1910 and before the Great Depression. The special order models are truly huge and heavy mechanisms and were introduced after the case design has changed to the satin nickel finish. The special order employed a slightly larger movement size 'R' from the company's previously largest movement, the 'M'.

This photo shows the slight difference in size between the two. ▲ Model N. ▲ Model N, special order for use with automatics.

This photo shows the slight difference in size between the two. ▲Model 6295 E.T.L., SIRIUS. ▲ Model 6370. Contemporary offering The SIRIUS was a short-lived entry into the fully electronic market. Electronic time locks have since proved to be less reliable than the old-fashioned mechanical designs and have largely been discontinued. The company's time locks have been built since 1978 in Lausanne, Switzerland. In 2005 after 140 years, S&G lost its independence and became a wholly owned subsidiary of the Stanley Works under the name of Stanley Security Solutions, Inc. Stanley retains the S&G trademark on their time locks and other security products. Below are a few interesting Sargent & Greenleaf time lock installations in safe and vault doors

Model #3

Model #4 Model "Cleoh"

Triple A Triple B

Triple C

Triple H Quad N |

.jpg)